Oxygen Conservation Strategies During COVID-19 Surges

Contributors: Richard Branson, RRT; Christian Sandrock, MD, FCCP; Dennis Amundson, DO, MS, FCCP; Asha Devereaux, MD, MPH, FCCP; Chuck Wright, MD; Jeffrey Dichter, MD, FCCP; Ray Daniels, RRT; Arzoo Salami, MD; Douglas Ornoff, MD, PhD; and Ryan Maves, MD, FCCP

Published May 5, 2021

Download and share this infographic

Download and share this infographic

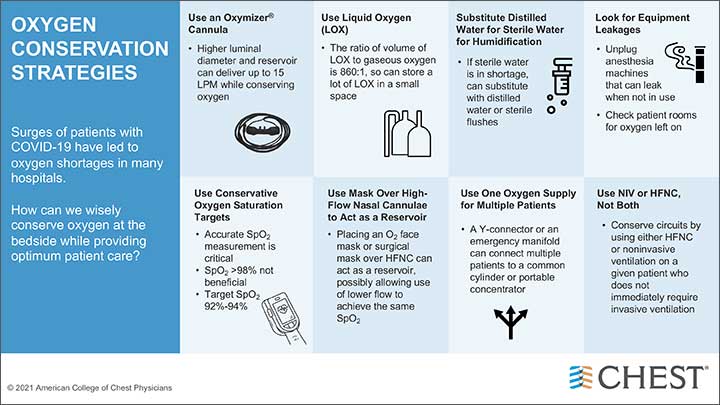

The idea of running out of oxygen seems strange to most clinicians working in North America and Europe, but surges of COVID-19 led to limitations in oxygen supplies in Los Angeles, other regions of the United States, and the United Kingdom during January 2021. Low- and middle-income countries, where medical equipment may be limited even in normal times, are facing an even more acute limitation of oxygen supplies. As COVID-19 is receding in many regions of the US, the epicenter of the pandemic has shifted in part to Brazil and India, where hospitals in those countries are facing unprecedented demand for oxygen supplies.

The normal abundance of medical oxygen means that clinicians have rarely needed to identify and employ strategies for conserving it. Clinicians and hospitals can utilize these key strategies to conserve and extend oxygen and other critical supplies for respiratory support, both for general use and during public health emergencies such as COVID-19.

- Use an Oxymizer® or similar reservoir device to conserve oxygen delivered via a nasal cannula. The Oxymizer has a higher luminal diameter, in combination with an incorporated oxygen reservoir, which delivers a higher FiO2 to the patient while using between 25%-50% as much oxygen from the tank as would be used through a conventional nasal cannula. Thus, oxygen is conserved and the flow rate can go up to 15 liters/minute.

- Use liquid oxygen (LOX). The ratio of LOX to gaseous oxygen is 860:1, permitting the storage of very large quantities of oxygen in a smaller container. Many skilled nursing facilities, as well as alternate care sites such as tent hospitals, will not have routine access to LOX, as it is mainly used in hospitals on the in-line wall system. LOX is readily available, however, and can be placed where it is needed, and LOX lines can be plumbed to patient beds.

- Mobile 3,000-gallon LOX units can be connected to a hospital’s secondary O2 system to refill as needed.

- Oxygen delivery can be hampered by shortages of sterile water used for humidification. In these situations, distilled water may serve as a substitute; respiratory therapists can save an empty sterile water bottle and fill it with distilled water.

- Hospitals should look at oxygen leakage from equipment. Anesthesia machines can be unplugged when not in use, as they may have been left on and have a slow leak of oxygen. Rooms with piped-in oxygen may be left on inadvertently as well; these should be inspected, including rooms where oxygen use is less frequent, eg, labor and delivery. Be sure to turn off flow to manual resuscitators that are not in use.

- Hospitals should survey the pipes that feed oxygen into potential high-demand areas, such as the emergency department and intensive care units. Hospital floors not built for ICU beds may not have sufficient oxygen flow to support multiple patients on HFNC. It may be necessary to change the pipes, which will add to efficiency in the end.

- A Y-connector can be used to deliver oxygen from a concentrator to two patients at a time who are on the same flow of oxygen. The FiO2 will be the same between the two patients, but flow will be reduced and will vary based on downstream resistance.

- It is not uncommon for patients to be switched between high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) oxygenation and noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV). As a result, HFNC and NIPPV circuits can be used up as patients are started on HFNC, then NIPPV, and then subsequently intubated. To conserve circuits, consider either HFNC or NIPPV for a given patient, and avoid both if you suspect your patient is going to require the ventilator.

- Deployable Oxygen Concentrator Systems (DOCS) can be placed in strategic areas or at large hospitals to refill H, D, and E tanks.

- Whenever possible, use evidence-based conservative oxygen saturation targets (eg, SpO2 92%-94%, rather than >98%).

- Use an O2 face mask or a surgical mask over high-flow nasal cannulae to act as a reservoir. This may allow use of lower flow to achieve the same SpO2. Surgical masks over HFNC may have infection prevention benefits.

- Large H cylinders can be fitted with manifolds to service multiple patients at the same time instead of just one.

- If there are enough portable oxygen concentrators, two can be used on the same patient (with a simple mask plus a nasal cannula) to raise the amount of oxygen delivered without having to use the hospital’s in-line supply or H, D, or E tanks.

- Consider using warm water sprinkler systems to keep the outside vaporizers from freezing during cold temperatures, as high oxygen demand may increase the risk of lines freezing, leading to shutdown of a facility’s in-line system.

References

Hospitals are running out of oxygen to treat covid-19 patients. The Economist. Accessed online on April 17, 2021. https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2021/03/09/hospitals-are-running-out-of-oxygen-to-treat-covid-19-patients

Blakeman TC, Branson RD. Oxygen supplies in disaster management. Respir Care. 2013;58(1):173-183.